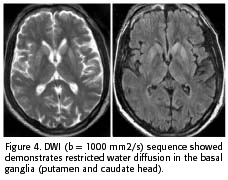

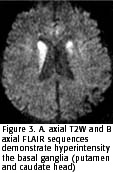

The MRI was performed at the presentation

and revealed hyperintensity of the basal ganglia

on T2W, FLAIR and DWI sequences. The T1W sequence showed a slight hypointensity of

the basal ganglia and no contrast enhancement

(Figure 3 and 4). The ADC was 0,44 x 10-3 mm2/s in

the putamen and 0,41 x 10-3 mm2/s in the caudate head, confirming restriction of water diffusion

(5). Basic biochemical and serological exams were performed and were negative.

At 6 months, the patient developed a complete irresponsible state, requiring respiratory assistance.

In January of 2003, a year and

ten months after the onset of symptoms, the patient was kept under intensive

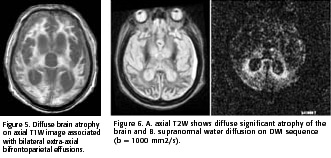

care and underwent a second MRI. The T1W images demonstrated diffuse

marked brain atrophy associated with frontoparietal subdural effusions

(figure 5). The signal abnormalities in the basal ganglia were no longer apparent on

T2W or DWI images (Figure 6).

In January of 2003, a year and

ten months after the onset of symptoms, the patient was kept under intensive

care and underwent a second MRI. The T1W images demonstrated diffuse

marked brain atrophy associated with frontoparietal subdural effusions

(figure 5). The signal abnormalities in the basal ganglia were no longer apparent on

T2W or DWI images (Figure 6).

Discussion

The classic triad of CJD includes rapidly progressive dementia, typical EEG findings (periodic sharp wave) and myoclonic

jerks. Both patients manifested these classical symptoms, fulfilling the clinical diagnostic criterias for CJD (1, 2).

Moreover, both patients showed signal changes on T2W and FLAIR in the putamen and caudate nuclei early in the course of the disease (2 to 4 months after first symptoms). In addition, the DWI sequence demonstrated restriction of the water motion in the striatum. The striatal hyperintensity could be seen early in the evolution of sCJD and supported the clinical diagnosis (2, 5-7, 9). The DWI is the most specific for the diagnosis of sCJD (2). Many diseases could manifest with basal ganglia hyperintensity on T2W, DWI and FLAIR images (ischemic, edematous, metabolic and toxic lesions, inborn errors of metabolism, Leigh's disease and mitochondrial encephalomyopathies in general), but these findings are transitory and observed in the acute phases of these diseases only (9). The persistence of the DWI hyperintensity images associated with typical clinical signs greatly suggests sCJD (2). Although, there are few reports about late phase of sCJD and we do not know for how long the restriction of water motion could be noted on the DWI.

Murata et al. (2002) discussed in their study the persistence of striatal and cortical hyperintensities on FLAIR and DWI images in the early and late stage of sCJD (2). In their study, the authors define the late stage of sCJD as more than 4 months after the onset of symptoms. Since the patient studied in our paper has such a long disease evolution and such profound brain damage, this might explain the disappearance of the striatal hyperintensities on T2W and DWI images. These suggest that the changes in the late stage of sCJD are unspecific and compatible with any encephalopathic process (8).

The origin of the basal ganglia diffusion abnormality in the sCJD is not well-known to date. Some authors have suggested that the vacuolar accumulation in the cellular cytoplasm could explain the restriction of the water motion on DWI (5, 6).

In conclusion, further studies are necessary to understand the pathophysiological mechanisms involved in the basal ganglia diffusion restriction in patients with sCJD. The role of MRI, mainly the T2W and DWI sequences is well established in the earlier stages of the disease process. In more advanced phases of the disease, when severe brain atrophy is often observed, the DWI sequence fails to demonstrate a specific pattern.

Bibliography available upon request.

Gratefulness: We thank Dr. Jeff Chankowsky for reviewing the manuscript and suggestions.