heavy

workload and helped generations of foreign neurological trainees and their

families adapt to North American ways. They had 4 children, moulded by their

happy home life. Although Robb never seemed quite certain about the role of

women in medicine, the eventual addition to the family of a physician

daughter-in-law seemed to tilt the scales in a favourable direction. Sociable

and friendly, a droll raconteur, Robb was a wonderful host.

heavy

workload and helped generations of foreign neurological trainees and their

families adapt to North American ways. They had 4 children, moulded by their

happy home life. Although Robb never seemed quite certain about the role of

women in medicine, the eventual addition to the family of a physician

daughter-in-law seemed to tilt the scales in a favourable direction. Sociable

and friendly, a droll raconteur, Robb was a wonderful host.

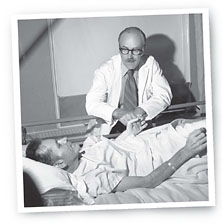

(Above) Preston Robb speaking with a patient, summer

1973. (Right) Dr. Robb with the Neuro Nurses in 1992.

In

1982 Robb was made Professor Emeritus of Neurology at McGill. He had always said

that he did not want to be under-foot when he retired as Neurologist-in-Chief.

True to his word upon retirement he moved to Lyn, Ontario

where he embarked on a second,

highly successful, career as Chairman of the Board of the family company and at

last had time to enjoy his hobbies of tree farming and wood carving.

During the long and satisfying years of our collaboration I came to appreciate

deeply two attitudes that set Preston Robb apart. The first was his desire to

understand the cultural and emotional background of his patients, often so

different from his own. This, he sensed, determined their reaction to

neurological disability in themselves and in their loved ones. The second was

his insistence that the physician do everything possible to create an

environment where patients and families were able to maintain their dignity

while coping with the dreadful hurdles that life placed in their path.

Preston Robb died at the age of ninety after a brief illness. He was in full

possession of his faculties to the end and gave a remarkable address after

receiving a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Montreal Neurological Institute,

just a week earlier.

6